“She never cooks,” he said, “and it’s been six weeks since there was laundry.”

Alice clucked her tongue from behind the bar, and no telling if it was for the idleness of Sanchez’s wife or the three-day complaint in his voice. He stared at her, his elbows splayed at a dead angle, and she stared right back ‘til he hid, shamefaced, in his beer.

“Don’t know what you want us to say,” she said, and rubbed detergent off the pint glass in her hand. Big Jake, two seats down the bar, snickered. He’d told Sanchez about his wife before the weather turned, hoping to gloat or maybe even to save him. If that’s what you like, he’d said, and picked up his end of the line pipe, and Sanchez had just smiled.

Sanchez wasn’t from around here. He’d come up from Vancouver to work fracking at Horn River, and moved from the Thriftlodge in with Betty Nosemaskwa at the height of July. The couple moved in a cloud of dark hair and gap-toothed smiles until the winter came on hard and early: thirty centimetres of snow in just September. It’d been drifts and chained tires ever since, and slowly, week by week, Sanchez started coming into Alice’s Neighbourhood Pub alone.

“Don’t want you to say anything,” he mumbled, four drinks and forty days into a silence that poured like concrete down his throat. Everyone in town had already had their say before the weather’d turned. He’d laughed it off to all of them; small towns had their politics, and he had Betty Nosemaskwa, her radiance, her sly warm jokes, her berry-red fingernails gesturing every time she spoke.

He couldn’t have said when she faded. Between the rolling heat of August and the September leaves, before the snowstorm, she had already retreated to the house, and then two rooms. Before he could trace what had come over her, if it had entered by window or door, she took to her bed and stayed there, and he was here, coping with the remains.

“You know what you do with an animal wife,” Jake said. “You take the pelt away; they always keep it close by. You hide that thing and she’ll smarten right the fuck up.”

Alice stiffened mid-inspection of her clean glass. Sanchez stared at her turned back as if to read its palm lines, and then swirled the bitter foam in his pint.

“Nah,” he said. “We’re not like that at all.”

*

The snow pressed close to his knees by the time Sanchez staggered up Betty Nosemaskwa’s front drive. The bungalow was sinking in a cold white desert: ice crept across the windows and vined the siding apart, and the front walk was a treachery of footprints. Sanchez spotted the red shovel handle three feet into a snowdrift: nose up, abandoned, and sinking fast. He stared at it a moment and gave up.

Inside the air was stuffy, the curtains rich with dust. Dishes lay in a scattered trail across the kitchen counter, stained with dried egg and ketchup. I begged her, just one sink of dishes, he thought, and pressed his hand to his forehead.

Betty was lost in the dim bedroom; lost in a landscape of sheets. They rucked about her knees and thighs in warm and private snowdrifts, and beside them, curled next to her, the brown bearskin spread its arms wide. It was the same shade as the delicate places on the insides of her wrists, the places he used to kiss and then wait for her smile to widen.

Sanchez was an only child; he had never learned to tiptoe. He toppled the overflowing trash can just three steps into her lair, and when he had righted it, Betty had opened her eyes. They were as heavy open as they were closed: dark brown and dull, eaten whole by pupil. Sanchez’s heart lurched. “Oh, querida,” he said. “You look so tired.”

“Mm,” Betty answered, low in her throat. She was never beautiful before her morning shower: her arms were seamed by blankets, her strong face reddened with sleep. Sanchez looked down at her, and the beer in his belly bloomed, tender and helpless and warm as the sun.

He brushed a tangled black lock off her forehead, and she sighed softly, nuzzled deeper into his hand. “How’re you feeling?” he managed, caught in her soft lashes on his palm.

“Tired,” she murmured, and her eyelids fluttered with anxiety. “I’m sorry. I’ll be much better tomorrow.” She held out both arms for him and he folded between them, folded against her drowsing skin and the bearskin between their hips.

There was a moment when it was all good again: wrists and foreheads, the thick abandon-smell of them, his thumb circling her right shoulder blade, her fingers tracing constellation lines between the sun-dark moles on his back. And then her breath drew heavier, crunched like snow beneath footsteps, and she was sleeping: drawn down again, drawn away.

Sanchez ran a hand over the dense, prickly fur. It was coarse-soft, tough down to the claws. There were lockboxes in the compressor station, built big for industrial tools. He could drive it out into the bush. Fort Nelson was surrounded by wilderness, land owned by numbered companies and ignored ’til the permits came through. Like as not, nobody’d ever find it.

He watched the pinpoint lines on her forehead smooth, and thought: The dishes don’t matter. He could shovel the drive tomorrow. He eased himself away from her with the greatest delicacy and wiped both hands on his jeans.

“Mm?” Betty said, and grasped at the cold where his body had been.

“Baby, don’t worry,” he said, and kissed her forehead once. “Go to sleep.”

*

Sanchez went to work the next morning sweat-soaked from shovelling, fossilized egg wedged under his nails. Big Jake caught him up at the tool locker. “How’s your woman?” He had not called Betty by her name since she and Sanchez took up together.

“Fine,” Sanchez said tightly, through his two knit scarves. The loggers had gone home when the snow drew deep. But Northland Resources had orders to fill before winter shutdown, and nobody cared if the floorhands got cold.

“Did like I said, hm?” Big Jake’s elbow jostled, threatening to go in for his ribs.

Once, when Sanchez was young and lost, he’d mistaken bright bluff confidence for knowing anything worth a damn. That had been years and miles ago. It was as far behind him as the Vancouver coast. Sanchez’s tongue touched his teeth, lingered, pulled away. “We’re not like that,” he repeated, and kept his gaze trained straight into the tool locker.

Jake Morris was not grasping the hint. He moved in closer. Sanchez felt, in the cold air, the radiant heat of his breath. “Like what?”

Sanchez turned full to face him, and tipped his chin up. “I don’t want a girl with me who doesn’t want to be with me,” he said neutrally, and pulled on his gloves.

Jake’s face darkened. “What’re you sayin’ about me there, chico? What kind of guy are you saying I am?”

“Nothing,” Sanchez said, and thought, you fat honky fuck. “I ain’t saying nothing.”

Big Jake Morris squinted at Sanchez through his flushed chipmunk cheeks, a distorted map of different wild land: red fault lines spilling heat into the pits of his nostrils, flared with uncertain fear and rage. “I love women,” he said. “I fuckin’ love ’em. You ask around. Ask anyone how good I am to a woman.”

Any comment would further inflame him. Sanchez picked up his helmet and started for the wellhead, leaving Big Jake to trail after him. “You ask,” he shouted, and then the sound drowned in the endless noise of the pump.

*

At the end of shift he drove the back way home, eyes on his rearview, looking for headlights. It would have been the first time someone tried it in Fort Nelson, but for Sanchez, it wouldn’t be the first time.

He pulled up at Betty Nosemaskwa’s bungalow under an undyed wool sky, the snow he’d shoveled last night ripe for replacement. There were new plates scattered across the living room table, freshly scarred with peanut butter and small raisins gone hard. Saskatoon jelly dripped like bloodstains across the blue melamine. He held his hands to his eyes to hold the tectonic pressure back: at least he knew she was eating.

The house hung still and dormant. He moved through it, an intrusion, and drew the blinds. She wasn’t better, but they’d both known it had been a lie.

*

November blew in like a death sentence. He felt the cold like nails digging in; so cold turning the door handle in the mornings burned. The job was over; even the company had scented the air, a sharp edge of woodsmoke and endless ice, and cut the seasonal men loose. There was nothing to do in Fort Nelson but lie low until spring.

In the heavy air of the back bedroom, Betty Nosemaskwa sank deeper and deeper. The pads of her palms felt like motorcycle leather. They scraped when she reached up to touch, fluttering, his cheek. “I dreamed about you,” she mumbled, still probably dreaming.

“Oh yeah?” he asked gently, and ran a hand down her unwashed hair. She spoke so little now. Her big-throated sunshine laugh felt like something he’d fabricated on a secondhand lathe down at the job site, conjured up from imagination and a stray long black hair to get through the endless nights.

“I dreamed you were carrying the whole of the world on a waterfall plate on your head,” she murmured, and I am, he thought: groceries cleaning heating working waking up alone in the dark. That night he dreamed it too: a universe balanced precariously on the spot where his brown hair was already thinning, and the muscles of his neck swayed in an Arctic wind. There were no safety cables on him. There would be no quarter if he dropped her.

He read everything there was to read about bears. Most of it was about how to scare them away: face them directly, make noise, fight back. Make yourself look big. He was a veteran of oil and lumber camps up and down the coast; he found nothing particularly inventive about the approach.

Fort Nelson had spotty broadband in the summer, with the horseflies out, and now that everything was buried under winter white it was worse. He downloaded wilderness videos an agonizing frame at a time, and listened to the clicks and small sounds bears made at play. When they blew air, they were anxious. Either Betty snored or the winter made her frightened all the time. He sat next to her on the musty bed, his hand tracing warmer languages on her back, listening for translation. He sang her sleeping songs she’d have understood if they’d grown up the same.

On the days he couldn’t take the silence anymore, he paged through a 1970s edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica in Alice’s back booth, nursing scrambled eggs and an oil-well headache, reading the entries on Indigenous folktales until he admitted he wasn’t reading anymore. He could go back to Vancouver, find a winter job in a warehouse or driving at a ski hill; buckle down in a rooming house and endure the rain. But each morning, he was still living in her house. The bills were still paid. Each evening, he sat next to her in the back bedroom, her sheets a raked sand garden, and whispered: “Betty, baby, what do I even do for you?”

He listened close to her soft sounds, uttered random or in a try at reply. She clung to him, whuffing like a wounded thing. Fear, he thought, with his stomach icing through. Anxiety. Fear. Betty’s eyelids fluttered, and Sanchez sat beside her, helpless, and held her limp and roughening hand.

*

The sun went.

“Ten, nine, eight, seven, six,” the man on the TV intoned, through the frazzled single speaker in Alice’s Neighbourhood Pub. In the darkness, the scattered singles of Fort Nelson and laid-off site workers lifted chipped glasses and dented cans. Their roar drowned out the last of the year: “Happy new year!” A burst of plastic confetti flew up and then fluttered down to the floor. Someone clapped him on the shoulder, and Sanchez, alone, squeezed himself smaller and ordered another pint.

“You should go home,” Alice said, an hour or more past midnight. He was the only one still in Alice’s Neighbourhood Pub. The storm was howling outside, digging fingers into every crack between wood and glass and brickwork. Anybody sane had finished their drinking at home.

“Don’t you think I know that?” Sanchez snapped, and let out a breath, and slumped. “I’m sorry. I shouldn’t give you shit.”

Alice had pursed her lips; ready, Sanchez clocked, to blow air in a preliminary threat. Plastic fragments stirred in the chill breeze prying through the pub’s glass doors. He picked a bubblegum-pink piece of confetti off the table and rolled it between his callused fingers. “It’s hard. This is hard. She should be here too.”

He saw the spasm across Alice’s face. Shut up, Sanchez, he thought fiercely, but it was too late. He was drunk, and he was uncontrolled as a geyser. “How can you say you love a girl when you can’t be what she needs? When you can’t even understand what she needs? Would it work,” he asked her, eyes on Alice’s shuttered dark ones, too demanding, too intense, too much, “if I was from around here?”

Alice drew a breath, and he shut his mouth, hard. They were walking perilously close to the tale everyone shrank from hearing but which needed, so badly, to be told: how there was so much love in him, dammed up, routed from its natural canyons, shoved underground, contained, and the pressure of it frightened him; it spilled, and spilled, and spilled. Every man in the cities or work camps he’d seen acted like it was fine, like they were smooth waters over a smooth riverbed, but in the moments any one of them looked it in the eye, they knew: if a man excavated that boundless love wrong, the explosions could wreck cities.

“I just want to love her,” he said, and tried, like he always had, to swallow that horrible loving back.

Alice’s hand eased around the neck of her broom. The women were always a little kinder in towns like this, except when they were differently unkind. “Go on with you,” she said, oddly, but it wasn’t the flat-angled face she reserved for Big Jake Morris.

The car was cold. It took the engine twenty minutes to warm. Sanchez sat behind the wheel, insufficiently sober, and leaned his sweaty forehead against the unworn country between ten and two. The light inside Alice’s flickered off, and then the light out front. Perhaps it would have been better if he had taken the skin and locked it away on the work site forty miles away. If they had done what men and women did, no matter how imperfect.

He’d spent time with men on the crews here and farther downriver: men who wanted him to dress wrong, eat wrong, sing along when they cranked their own music too high as if he’d always known the words. It wasn’t that they hated him; it was just so they could like him in the only ways they understood. How could he not want to be liked by them, after all? What cost was a skin compared to that?

He heaved a breath, sick-scented: car heat and old upholstery. He could not ask her to be any different. It was her body doing this. It was her own skin.

Inside, the house was so warm. The smell of unruly bodies hung in the air sweet and definite, a promise not written in languages he knew but which pulled him, regardless, closer. He shed socks and sweaters as he made his way down the undusted hall to the bedroom, where the shell of the woman he loved had laired. His outdoor clothes left a trail through the disused front rooms of the house.

It was by moonlight he saw it curled among the blankets; by moonlight and the arc of one weak lamp: a soft-breathing brown bear, black nose atwitch, its long lashes just as girlish as Betty Nosemaskwa’s eyes. It slept with one paw stretched out: reaching for a ghostly source of warmth abandoned between the stained sheets. It was her, he thought, through the reflexive amygdalian terror, reaching for him: musky, unknowable, and still so recognizably her. Still tinged with sweat and baby powder; still soft in the tiniest places between paw pad and flexed ankle. That damp nose flared when he lingered at the doorway. A huge eye opened, unfamiliar, and fixed on him with pained, frustrated love.

“Bet,” he said softly. The warm bulk of her huffed an anxious sigh, and buried her face in the sheets. He held out his hands, not a dominance stretch but an offering. There is a bear in your bedroom, his animal brain shrieked, and the adrenaline was sparkling confetti in his vision, and when she saw his hands she wailed, a short, sharp howl of distress that shook the walls and shook his bones.

And then his voice was joining, a furious sob that rang in chorus octaves higher, and he was across the room and whispering with hands and skin, the only language they had left in common: I love you. I love your bearness. I love every hair of you, I love you happy, I love you sad, and I miss you so much it’s destroying me.

Men didn’t speak those kinds of words, but they weren’t like that. He could not map what they were like, or describe it to passersby, but even languageless and ursine, the sight of her made him want to pour out pine needles for a soft bed, feed her horchata to see her eyes change at the taste, run his fingers over the joins and tendons of her world and guide her hands through his. Oh, god, he wanted to never be bored of her.

The bedside lamp shuddered and then it was loose, the secret part of him, the thing that shifted continents and left wreck rock and poisoned water behind. The pressure of his boundless love was filling the close bedroom, spiraling five hundred feet into the dark grey sky, a leviathan loosed upon the both of them, enough to blow the foundations outward. Sanchez and Betty Nosemaskwa looked at each other as the laundry blew back against the baseboards, as the 1960s paisley wallpaper fluttered and caught at its loose corners.

“I miss us,” he said, and his eyes were stinging.

She drew a deep cyclonic breath and clicked at him softly with her long tongue.

The ground bucked. He buried his hands in her brown fur and held on. Hands and skin and grief were still a language. They were still a den two people could inhabit together, and if they were together, they could stand hip to hip and dig outward until the air licked spring. Her paws were sure through the snowbanks. His legs, strong from bush work, gripped steady on. The snow swirled down outside, and then inside, and then upon his cheeks, and they were moving down the darkened streets, through the stormlight, holding on for dear life.

When they got to the river the ice was cracked, the water moving. It trickled sluggish. Her skin was warm. He did not know what lay across that border. He had never traveled nightwise this way, out of Fort Nelson, due north.

The plume was still behind him, a burst well in the sky; Betty Nosemaskwa’s house a little fish atop it, balancing by the tail. And he understood, abruptly, that they would find it when it landed—by whatever combination of noses, hands, and feet. She wouldn’t leave him to the cold.

Sanchez sat back on his heels like a fisherman, patient, and her paws carried them outward under the dazzling white sky: past the work site, past the maps, onto the frozen river, walking, together, across the treacherous ice.

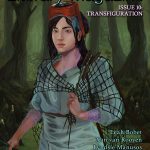

Novelist, editor, and critic Leah Bobet’s novels have won the Sunburst, Copper Cylinder, and Aurora Awards, been selected for the Ontario Library Association’s Best Bets program, and shortlisted for the Cybils and the Andre Norton Award. Her short fiction has appeared in multiple Year’s Best anthologies and been transformed into choral work, and is taught in high school and university classrooms in Canada, Australia, and the US.

She is guest poetry editor for Reckoning: creative writing on environmental justice’s 2021 issue.

She lives in Toronto, where she makes jam, builds civic engagement spaces, and plants both tomatoes and trees. Visit her at http://www.leahbobet.com.

Photo by Olen Gandy on Unsplash

Creator Spotlight:

Leah Bobet

Author of “The Bear Wife”

What inspired you to write this story?

Animal-wife stories always go the wrong way for me–or they stop too early, at the obvious problems. There are so many other things that happen in a marriage besides shiftiness and force: obstacles, goals, problems you tackle where both people mean well and are hurting. They should have stories too, I think.

What do you hope readers take from this story?

Whatever they need, now or later.

To give other writers hope, would you mind sharing with us how many edits and/or submissions this story/poem has been through?

“The Bear Wife” had one revision, and sold on its fifth submission–and spent seven years in a file on my desktop between writing the first paragraphs and the last. It was a long problem, but on the inbound rather than in the submission stages.

Recommend something to us! This could be a book, a short story, a video game, a project you’ve heard about, something you’re working on, etc. Anything that has you excited and that you want people to know about.

I’d love to send more attention to the New Decameron Project. It’s a a collection of daily free short fiction to get us through a plague year organized by Maya Chhabra, Lauren Schiller, and Jo Walton, with tip jar proceeds going partially to the authors, mostly to Cittadini del Mondo, a library and refugee clinic project in Rome which needs extra support in the current crisis. There’s a magnificent list of contributors donating their work, and it helps our most vulnerable.